Tragedy and Disaster

20th April, 2020 – Cotignac

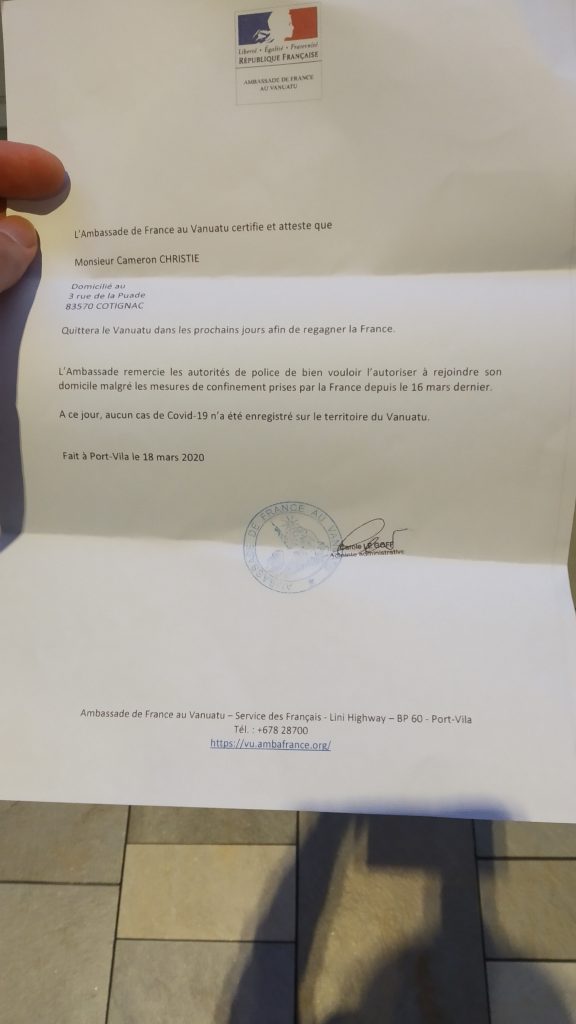

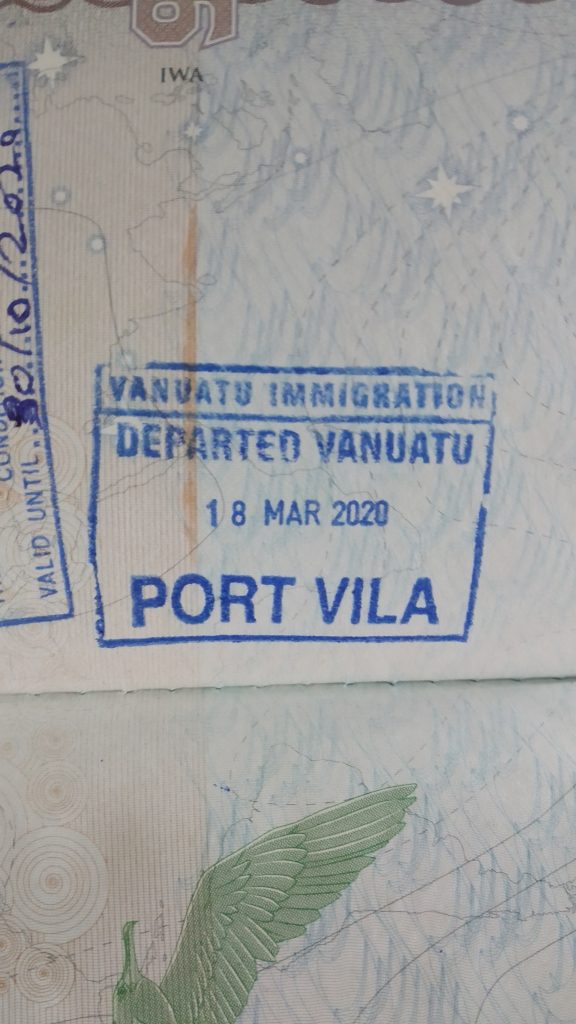

It has been a while since I’ve written a blog post, as the in-country part of my assignment in Vanuatu was cut short, much to my mother’s regret. On arrival back in Cotignac, I was put in the house next door for two weeks quarantine. You all know what lockdown and quarantine feels like, so there’s little point me posting our shared experiences.

I made use of my time in the other house to assist a Vanuatu-based UNICEF volunteer (one of the ones who decided not to disappoint her mother and stay on) to translate the Vanuatu public health authority’s official guidance on COVID-19 into French. Whilst everyone in Vanuatu speaks either English and Bislama or French and Bislama, there aren’t so many who speak English and French, and given the public health authority was working flat out with its response to COVID-19, they reached out to anyone who might be able to help. As part of this work I came across some linguistic curiosities. Did you know, for example, that the WHO (OMS in French), has chosen the acronym COVID-19 to be of the feminine gender, whereas almost all other sources refer to it as “Le COVID-19”. Usually, loan words and acronyms from other languages into French are assigned the masculine gender, so it’s an interesting choice by the WHO translation team. Those of you reading this who speak French, please do let me know your views on the matter.

Now the COVID-19 situation in Vanuatu is that there is not a single positive case. In order to keep things that way, shortly after I departed the country, all international air traffic was interrupted, and all passenger boats refused entry. This is an understandable reaction to the pandemic, and I commend the prompt action of the interim government which has ensured the country remains one of the few virus-free nations on Earth. However, subsequently, further measures were imposed which seem bizarrely disproportionate. Schools were closed. Domestic flights and passenger vessels were also discontinued. An overnight curfew was imposed. Every mobile phone owner was supposed to register their SIM card with a government register by the end of April. I don’t even understand how that last one could possibly help as a public health measure.

In any case, just as I finished my translation work on a Friday evening and sent it for proofing and publication the following week, there was news of a cyclone near the Solomon Islands which had the potential to move over Vanuatu over the weekend. Tropical Cyclone Harold gained more strength than initially forecast, and by the time it made landfall over the Vanuatu archipelago on Sunday evening / Monday morning, it was a category 5 (out of a possible 5) cyclone. This means sustained winds in excess of 215km/hour, with gusts in excess of 250km/hour. In non-numeric terms, this means winds likely to result in widespread destruction to property and significant loss of life, the most violent storm which can possibly exist on the planet. The path of the cyclone in Vanuatu started in West Santo, passed directly through Luganville, before moving down to the Southwest, crossing the North of Malekula, and across West Ambrym and Pentecost before moving onward to wreak further havoc in Fiji. Communications went down when the storm hit, and although they are now mostly back up again, the full extent of the damage has yet to properly be assessed. The town of Lakatoro on Malekula, where I had been based, was sheltered by the surrounding foothills, so apparently escaped the worst. I have since spoken briefly with Kevin, and he tells me he and his family are safe. To give an idea of the devastation, here are some photos from facebook of the former town of Melsisi, on Pentecost Island:

It is clear that rebuilding after a cyclone of this magnitude is a huge task. The most pressing issue to prevent further death is usually the availability of clean water, and an often overlooked effect of a cyclone is the devastation it wreaks on the food supply as crops are ruined. Gaps in the water and food supply are typically plugged by bringing in supplies from unaffected regions, but efforts to do so were of course initially hampered by the COVID-19 restrictions and their impact on logistics. Most of the restrictions have since been lifted, although international flights are still prohibited except under the most stringent of conditions, so international aid and particularly international expertise are slight.

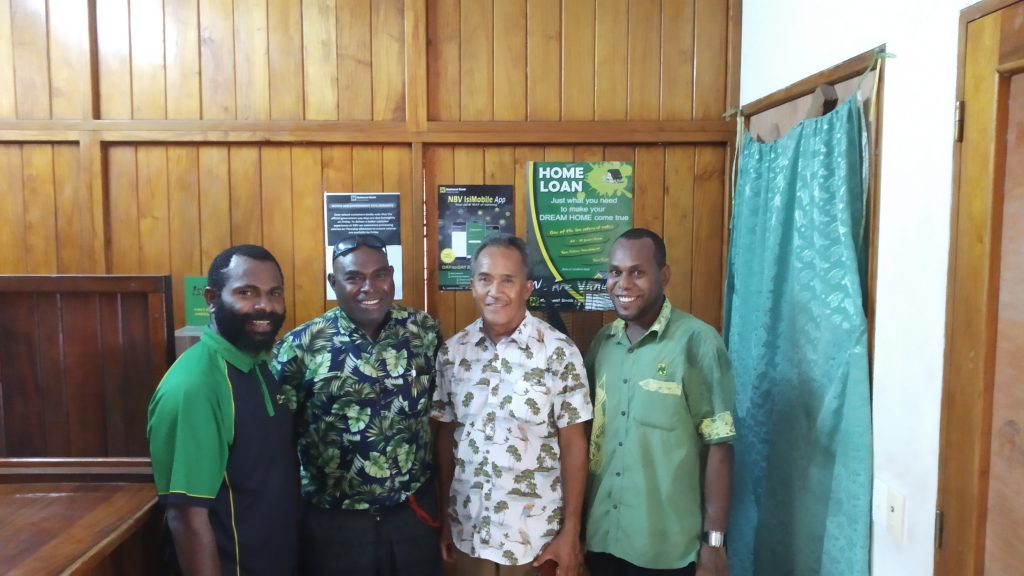

The translation work I had accomplished for the public health authority presumably was pushed to the bottom of the pile. Any work I did with Kevin on the investment policy for Malampa province can presumably be shelved for quite some time, as investment into the province will not show any noticeable signs of activity for the forseeable, although the brief contact I’ve had with him since suggests that he wants me to carry on drafting the policy, so that at least they have something in place when the time comes. The Vanuatu peanut butter industry will not become the next big thing as so badly hoped by my brothers. Eating bats is also quite likely to be frowned upon in future.

I had mentioned in my previous post that all VSA volunteers worldwide were being called back to New Zealand, as the cessation of flights meant secure operations could no longer be relied upon. As I arrived back in France, the other volunteers were making their way to Port-Vila and most of them were scheduled to fly out on the last plane from Port-Vila. Unfortunately, without warning, Air Vanuatu cancelled this flight, and grounded its fleet a few days earlier than scheduled, trapping 11 of my colleagues in country, and it was then that cyclone Harold hit. Following the cyclone (which caused no damage in Port-Vila, as it passed a bit further to the North), the New Zealand government negotiated the safe entry of a Hercules C130 RNZAF to Vanuatu, to bring supplies to assist with the recovery, and on the return leg they “rescued” those of the 11 who chose to be repatriated. Commendably, or perhaps foolishly, the VSA programme manager Trevor and his wife Michelle chose to stay to help out with recovery efforts as best they could. A couple of others among the 11 also decided to stay. Hats off to you guys, my mother would be proud of you.

It is a privilege to be alive, with clean water to drink, plentiful food to eat and a roof over my head. I truly wish all ni-Vanuatu could say the same. It was also a unique privilege to have shared their country and community for a couple of months; it is such a pity my visit ended in such disastrous circumstances. May the resilience of the Ni-Vanuatu shine strongly in the times to come.